Long before Christopher Columbus boarded a ship, Vikings sailed across the Atlantic and arrived in North America. Proof of this mission can be found at L’Anse aux Meadows, an authentic 11th century Norse settlement in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada’s most easterly province. These excavated remains are evidence of the first European presence in North America.

The site was excavated in 1960 when Norwegian explorer and writer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, searched the area. It was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1978.

This remarkable archaeological site consists of eight timber-framed turf structures built in the same style as those found in Norse Greenland and Iceland from the same period. In addition, many artifacts, including those related to iron smithing, a stone lamp and sharpening stone, are on display.

The thick peat walls and turf roofs appear to be a smart defense against the harsh northern winters. Each building and its rooms are set up to showcase different aspects of Norse life and interpreters dressed in Viking garb tell entertaining and informative tales.

Getting to L’Anse aux Meadows is not an easy feat. It is at the northern most tip of the island of Newfoundland, most easily accessible from the St. Anthony Airport, or a 10-hour drive from the provincial capital of St. John’s. http://www.tripsavvy.com/historical-sites-in-canada-4153603

Archaeological site of L’Anse aux Meadows, a Viking settlement in Newfoundland, North America, which was built and occupied around 1000 CE. It could house up to 70-90 people who would use the site while on expeditions lasting a few years. L’Anse aux Meadows likely functioned as a sort of gateway from which Norse work crews undertook trips to other areas such as the Gulf of St Lawrence, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Labrador, and Baffin Island, where they gathered resources to bring back home to Greenland and beyond.

L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site in Newfoundland

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():gifv():format(webp)/GettyImages-177885248-5952e6ea5f9b584bfe6f750e-e7e6adcb00aa4c0994660a15864674d0.jpg)

A visit to L’Anse aux Meadows (pronounced “lance oh Meadows”) is not only a step back in time, it is a journey to the meeting of the Old World and the New. From common ancestors, two groups of humans traveled in opposite directions – one through Africa, Asia, and Europe, then by boat to the Americas, and the other from Africa to Asia and across a land bridge to Alaska and the New World. At Newfoundland’s L’Anse aux Meadows, you can see the place where the two met for the first time since their original parting of ways. Take a photo tour of L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site.

L’Anse aux Meadows is more than a National Historic Site, it’s also a modern-day village at Hay Cove, with places to stay and eat and plenty of natural beauty.

The Norse settlers weren’t the only people to find L’Anse aux Meadows a good place to live and fish. Native People first settled here around 3950 B. C. Leifr Eiriksson (Leif Ericsson) and his band of Norse settlers was latecomers to L’Anse aux Meadows, arriving here around 1000 A. D.

n 1960, the archaeological remains of Norse buildings were discovered at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Until recently the settlement date was estimated within about a sixty-year span around 1000 CE. On Wednesday, scientists published a study in the journal Nature pinpointing the arrival date to 1021 CE, or 470 years before Christopher Columbus reached the Bahamas in 1492.

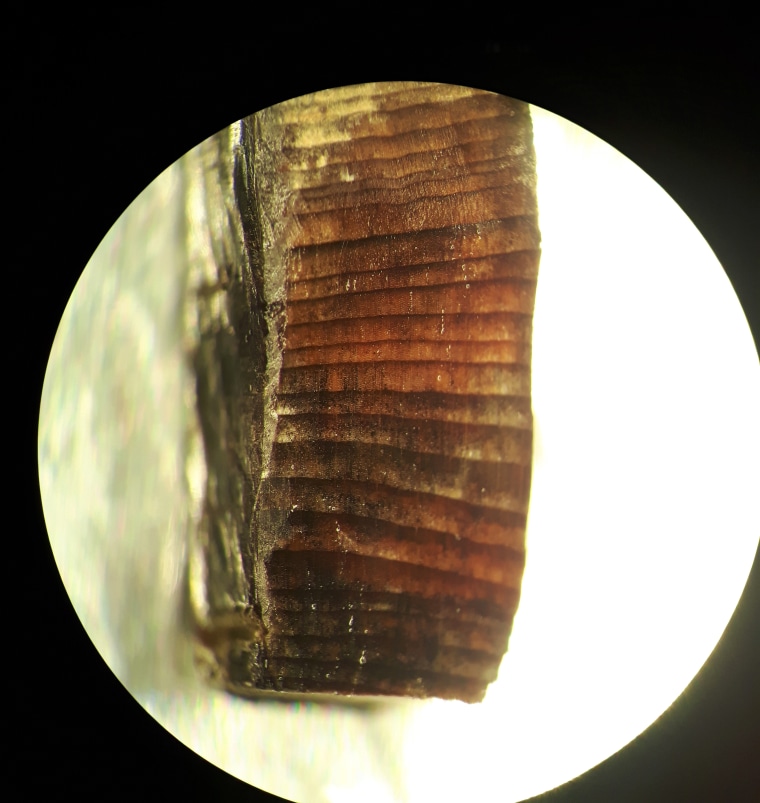

Archaeologists identified three trees at the site that were cut with metal tools, which the Norse had, while indigenous peoples did not. The archaeologists were able to accurately date when the trees were cut based on markings on the tree rings from a rare solar storm — called a Miyake event — that took place in 992 or 993 A.D. With the date of that inner ring fixed, “all you need to do is count to when you get to the cutting edge,” said Michael Dee, a study co-author from the University of Groningen.

Until now, the dates for when L’Anse aux Meadows was settled were “guesstimates,” Sturt Manning, an archeologist and director of the Cornell Tree Ring Laboratory, told The New York Times. “Here’s hard, specific evidence that ties to one year.”

The Norse voyages to Newfoundland are mentioned in two Icelandic sagas, which indicate L’Anse aux Meadows was a temporary home for explorers who arrived in up to six expeditions.

The first was led by Leif Erikson, known as Leif the Lucky — a son of Erik the Red, the founder of the first Norse settlement in Greenland.

L’Anse aux Meadows, too, was expected to be a permanent settlement, but the sagas indicate it was abandoned due to infighting and conflicts with indigenous people, whom the Norse called skræling — a word that probably means “wearers of animal skins.”

In tree rings and radioactive carbon, signs of the Vikings in North America

Vikings from Greenland — the first Europeans to arrive in the Americas — lived in a village in Canada’s Newfoundland exactly 1,000 years ago, according to research published Wednesday.

Scientists have known for many years that Vikings — a name given to the Norse by the English they raided — built a village at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland around the turn of the millennium. But a study published in Nature is the first to pinpoint the date of the Norse occupation.

The explorers — up to 100 people, both women and men — felled trees to build the village and to repair their ships, and the new study fixes a date they were there by showing they cut down at least three trees in the year 1021 — at least 470 years before Christopher Columbus reached the Bahamas in 1492.

“This is the first time the date has been scientifically established,” said archaeologist Margot Kuitems, a researcher at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and the study’s lead author.

“Previously the date was based only on sagas — oral histories that were only written down in the 13th century, at least 200 years after the events they described took place,” she said.

The first Norse settlers in Greenland were from Iceland and Scandinavia, and the arrival of the explorers in Newfoundland marks the first time that humanity circled the entire globe.

But their stay didn’t last long. The research suggests the Norse lived at L’Anse aux Meadows for three to 13 years before they abandoned the village and returned to Greenland.

The archaeological remains are now protected as a historic landmark and Parks Canada has built an interpretive center nearby. It’s listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The scientific key to the exact date that the Norse were there is a spike in a naturally radioactive form of carbon detected in ancient pieces of wood from the site: some cast-off sticks, part of a tree trunk and what looks to be a piece of a plank.

Indigenous people occupied L’Anse aux Meadows both before and after the Norse, so the researchers made sure each piece had distinctive marks showing it was cut with metal tools — something the indigenous people did not have.

Archaeologists have long relied on radiocarbon dating to find an approximate date for organic materials such as wood, bones and charcoal, but the latest study uses a technique based on a global “cosmic ray event” — probably caused by massive solar flares — to determine an exact date.

https://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/tree-rings-radioactive-carbon-signs-vikings-north-america-rcna3383?cid=sm_npd_nn_fb_ma&fbclid=IwAR3StOwNfeMWTxiGJkiWFaLalgeG1PBS0tIYbyQuYpSy59K3SK9js7ubTds